Photo: Liza Francois

Represented by KETELEER Gallery in Antwerp

& Thomas Rehbein Gallery in Cologne, Germany

Letter to: Joëlle Dubois

In 1863, Charles Baudelaire published a series of essays under the title Le Peintre de la vie moderne – call it a manifesto for modern painting. Painting referring to Greek and Roman antiquities is over, gone are the genre paintings with characters dressed in mediaeval robes. Charles Baudelaire made a case for a movement in painting that stands for the now – painting habits of the present – with a pronounced focus on urban life, the contingent, and the fleeting. According to Baudelaire, beauty had to be found in one’s attire or facial features, elements that are inseparable from the world we live in – the Zeitgeist, in other words. More than 160 years have elapsed between the publication of Baudelaire’s essays and my visit to Joëlle Dubois’ studio on 14 October, but what Baudelaire wrote is still readable, relevant, and applicable today – certainly in relation to the work of Joëlle Dubois. So the NOW! During this visit, Joëlle was in full preparation for her exhibition Forget Me Not at Keteleer Gallery, an exhibition one could call a visual narration about forgetting and loss, prompted by the debilitating and lingering Alzheimer’s disease that held Joëlle's mother in its grip. The crossed hands in The Expectant Mother (2022), a portrait of Joëlle’s mom, instantly takes me to Portrait of the Journalist Sylvia von Harden (1926) by Otto Dix. Something about the paintings of Joëlle Dubois reminds me of Otto Dix’s work. Maybe it’s the way colour is allowed to be graphic, or how human warmth is made to coldly grate. Otto Dix holds trauma from the First World War in his brush, Joëlle Dubois the unmanageability of our digital present. For both of them, painting seems to be a way of creating order within themselves and the world surrounding them. That this kinship is significant – or perhaps it is better to speak of an “admiration” that Joëlle Dubois has for Otto Dix – is shown by the 10 x 15 centimetre panel Modern woman in the 21st century, ode to Otto Dix from 2018. Dubois copies Dix on the size of an iPad, showing that, just like Otto Dix, she is looking for a new objectivity. At first glance, Joëlle Dubois’ objectivity appears light-hearted, playful, erotic, and libertarian. But titles like Girls on Tinder, Corona Kiss, Junkfood and Videogames, Am I woman enough for you?, The camera is obsessed with what it sees, Free the Nipple and Toilet Paper Panic display Joëlle Dubois’ immediate involvement with the now. Each panel is a contemporary genre piece, a frozen fragment of the life of young and developing identities that are tossed back and forth between digital expectations and the imperfect everyday reality. Joëlle Dubois paints the archetypes of our time (social media, loneliness, identity, body shaming, the pandemic…) in situations that hover between playfulness and personal micro-tragedies, widely recognisable to almost everyone, and therefore also to herself. Otto Dix wanted to paint journalist Sylvia von Harden, because she embodied so much of her time. Joëlle Dubois paints every scene because it exudes everything of this time. In The camera is obsessed with what it sees Joëlle Dubois shows the complex relation between our identity, expected forms of beauty, and the all-consuming jaws of our smartphone. The smartphone in this painting is like the mirror held by Cupid in Diego Velasquez’s Rokeby Venus (1647-1651). Smartphones are today’s mirrors, and, like mirrors have always done, they distort and mislead. The camera is obsessed with what it sees shows us, however, a mirror that is watching, a mirror with eyes, with expectations and an opinion, a mirror like a knife. Attributes in this work are books (analogue wisdom), black flowers (surrender and devotion), and dominoes (luck and coincidence). The smartphone sheds light on the character’s face, and chains the pose of the black-haired woman through its digital eye. Today we seem to exist within two worlds, without knowing which of these two is most satisfying to us. The latter is perhaps a feeling that can be found in many of Joëlle Dubois’ works; that of being displaced, of losing oneself while searching, of being “in between”. The artist uses shining beauty to evoke forms of dark contemporary melancholy. And then there is Milo the dog. I don't necessarily want to talk about the special portrait that Joëlle Dubois painted of her dog. That would lead me to elaborate on the dog paintings of, among others, Pierre-Auguste Renoir and David Hockney – by the way, the artist has also paid homage to the latter with The man in the room, ode to Hockney (2021). Nor is it my intention to talk about our mutual fascination with furry four-legged friends. I do, however, want to talk about something that occurred to me during my studio visit, when Milo was resting like only dogs can – that the relationship between spectator and painting is very similar to that between people and dogs. So long as dogs have been domesticated, man has been painting, or leaving any kind of trace. Dogs have evolved an additional eye muscle that lends them a piteous glance, painters have been painting for centuries to undress our vision, thinking, and feeling. That is what Joëlle Dubois does with me as well in a dark yet playful manner.

Philippe Van Cauteren (S.M.A.K. Museum), Ghent, 5 November 2022

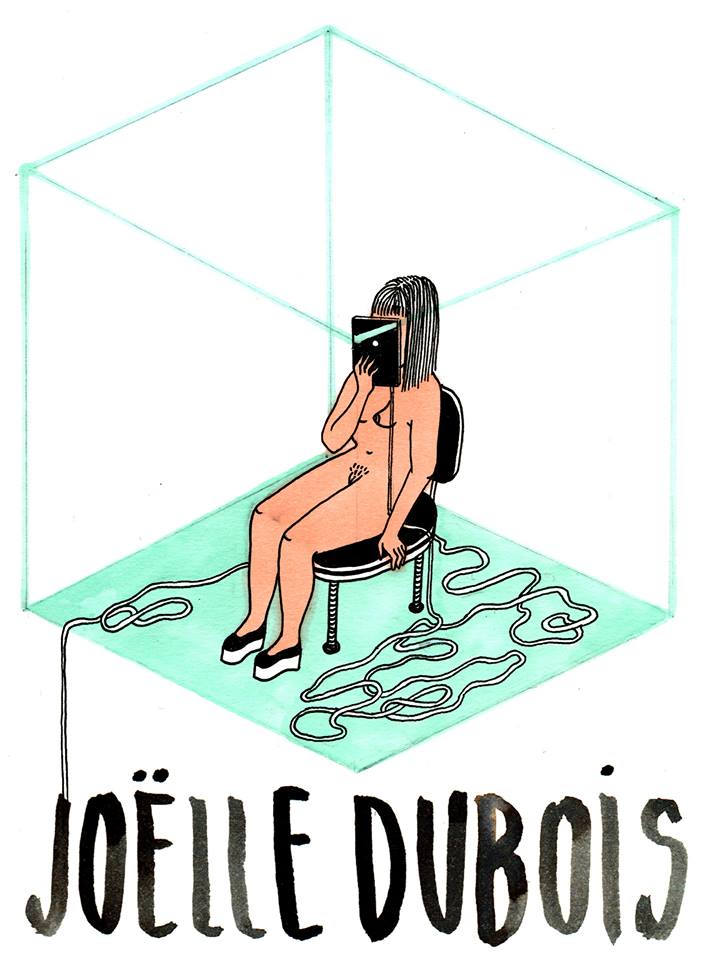

Joëlle Dubois’ (°1990. Ghent, Belgium) bold, colourful and glossy paintings are a feist of ambiguities. Taking social media’s effect on predominantly female users’ lives as a main theme, Dubois explores the digital maze running through these women’s very real lives. Irreversibly integrated in their homes, daily rhythms and sense of selves, smartphones have become portals to an inevitably elusive world of ideals dictating everything happening offscreen. Addicted to social media, endlessly scrolling through images, staring at others – and in so doing at themselves – these women seem caught in an endless quest for both the ultimate liquid* version of themselves and a daily satisfactory amount of social contact and confirmation.

In looking at things, we communicate with those things. We (sub)consciously react to everything we see by recognising ourselves in it (or not), taking a stance, having an emotional reaction to it,… No matter how insignificant an image may appear, we always become involved. Dubois’ works point to exactly this: how what we see influences how we are, feel and act; how everything we look at thus infiltrates our whole being and sense of reality.

She often paints women half naked – exposed and made vulnerable by all they’ve seen and projected onto themselves – with unshaven legs, in unflattering poses, chubby legs…. relentlessly comparing themselves to the images on their phone. When engaged in social events, even the most intimate, they’re never really there, but always there. A mixture of hope, feminism, obsession, apathy, superficiality and realness depicts today’s frantically confused zeitgeist. With her unique visual language, inspired by Japanese erotic block prints, Dubois nevertheless manages to use the countless ambiguities in her works for good. The naivety of the characters points to a dazed but persistent quest for human connection, some sort of authenticity and understanding. Dubois exposes harsh realities but manages to keep things light and hopeful even when they appear bleak and desperate, evoking a sense of compassion rather than cynicism.

- Lauren Wiggers, (Keteleer Gallery, 2021)

JOËLLE DUBOIS paints and illustrates. With a wink she transfers the digital revolution and the resulting role of humans in our modern society into her works. The Gent-born artist is especially interested in the voyeuristic aspect of digitalisation. Social Media Platforms such as Instagram, Snapchat or Youtube, television programs such as Big Brother or the Bachelor fulfill our desire to anonymously observe others in their suffering, their love life, their failures and also their successes. Digitalisation has made communication faster, more purposeful and interactive. However, this also goes along with the fact that less and less privacy is possible, and that one presents him/herself more openly and more naked to

everyone else. Basically communication is increasingly superficial, impersonal and anonymous. Dubois devotes herself with passion to this complex of topics in an ironic and also comical way. She depicts her protagonists in an exposed and unadorned manner, steeped in a drastic realism that often turns out to be very distorted and untrue in the digital world. By showing hairy, obese women and men in compromising positions, she emphasizes her own strong role as an independent and emancipated woman and artist. For all that, Dubois herself is a silent observer, watching the world in her own display of idiosyncratic perfectionism.

- Sylvia Rehbein (Thomas Rehbein Gallery, 2020)

With its glass touchscreen the technical artefact called Smartphone, is the perfect permeable digital membrane between public and private space. The constant connectivity of social media is increasingly blurring that line. The constantly multiplying apps on the home screen generally promise social contacts, interpersonal communication and longed-for closeness. By hastily swiping to the left or right on dating apps, every second you judge others attractiveness and compatibility when it comes to sexuality and life planning. On the other hand, on audiovisual platforms a staged unrealistic and simplified self is being shared with a faceless mass of followers that critically evaluates every pose and mien. All of it is anticipated by the user’s consensus – an agreement to the current purport of a flaunted surface that is more important than attackable depth.

In her works, Joelle Dubois primarily negotiates the absurdities of the following a preceding supposed self-optimisation. Her mostly female protagonists are of multi-ethnic origin and often contradict the standardised ideals of beauty. They are, if any, scantily dressed and think themselves safe in the remoteness of a colourful but ambiguous world, so to say post-digital beyond public and private space, always technologically connected and therefore exposed on the World Wide Web.

Furthermore, the artist’s new works are strongly influenced by personal memories and experiences. They explore the fields of femininity, fertility, loss and sexuality, which are symbolically inscribed into the images that await to be deciphered. In the pictorial narrative the voyeuristic view to intimate moments simulates truthfulness, while the character’s nudity makes them deeply vulnerable. Yet the ubiquitous occupation with the smartphone or similar tools makes the character’s aura pulsate between ignorant obsession and the saddest apathy.

Moreover, Dubois is testing another medium for the exhibition. The delicate acrylic paintings on wood are countered by the fast line of ink drawings for the first time. The format of the paper dictates the content, as it were: naked, female bodies, but curved and limited in height and width to the sheet size. Trapped in this space defined by the artist and thus only confronted with themselves, the women use the still omnipresent smartphone to ask questions about their own sexuality and weigh them up against the unrealistic expectations placed on them by society. Here, her own obsession with technology is usefully converted, a positive view that the artist shares as well: according to her own statement Dubois also uses her smartphone almost obsessively. On the one hand as an archive, with which she explores her own biography, looking backwards. In addition, the device opens up communication options, even outside of your own comfort zone.

More risk than danger, here and everywhere, superficial and deep at the same time. This makes Joelle Dubois an exact observer of today's society. And of herself.

- Maurice Funken (Artdirector Neuer Aachener Kunstverein, N.A.K.) December 2019

BEYOND VIRTUAL RELATIONSHIPS

New developments in technology and culture often generate both emancipation and new alienation. Worn-out forms of oppression give way to modern tendencies that entail an unknown threat. The first waves of feminism were accompanied by the emergence of a public, film industry, and pornography that greedily displayed the female body as a covetous object. While the post-feminist wave is responding to the aforementioned excesses, a voyeuristic tendency in social media is on the rise. What happens to the female body is even more true for exoticism. The paradisiacal representations of Orientalism did not stop colonialism. Once exotic glamor and patronage have disappeared, we regard other people as dangerous competitors with questionable principles.

The concept of intimacy also changed over time. Our vulnerability gradually became anchored in other people, objects and cults. What we have previously protected as a threatened territory (e.g. living room or naked body), we now voluntarily throw in the virtual space. Often these protected places have become formalisms, whilst our contemporary intimacy is looking for other places. We think we can get a glimpse into the deepest feelings and the brains of others through the new media, while staying safe in our living room. The Internet encourages us to explore "unknown horizons". But as soon as we look for personal contacts, our body comes into play

The medial glasses give users high physical expectations, as traditional media have always cultivated ideals of physical beauty. The contact seeker competes with the body profile of countless others. Thus, the communication falls into a cultivated superficiality. The media revolution also includes positive aspects for intimacy. In the long term, users learn to put corporeality in perspective, just as previous generations have been fed up with television images. The participants learn to get in touch quickly with a multitude of people and to critically evaluate them. The virtual contacts also leave traces, since the iPhone acts as a picture archive of the contacts.

All these themes can be found in one way or another in the acrylic paintings by Joelle Dubois. Art is a measure of social development. It registers and comments on our behavior. Dubois's compositions evoke a whole series of observations that lead to the analysis of our virtual experience. It could be the pictures that appear on an iPhone, but then as condensed scenes. In fact, attention is shifted from the digital screen to the experience space through colors, lines and shapes. Attitudes and faces reveal the psychological effect of communication, objects clarify the context. It quickly becomes apparent that the protagonists deviate from the false optimism expressed in advertising images. Although the warm colors suggest a world of glamor and seduction, we still see loneliness, fear or anger in the faces. Clothing and decor are rather cheesy than luxurious. These pictures show that "chatting" means more than pouring out one’s heart. It also determines our manners and timing. The anonymity of the city is extended to the virtual city.

This creates a freedom without history and social connections, which nevertheless is of great importance to society, not necessarily in what is said but in how it is said. It is difficult to find a greater contrast between the volatility of technological devices and a painting that requires the concentration of time and craftsmanship.

Interacting with other cultures, Dubois' work refers to history, creating an analytical distance to the virtual culture into which we are immersed.

- Filip Luyckx, curator, 2019

In her work, Joëlle Dubois examines the impact of social media without subjecting it to any explicit critique. She observes the (unusual) human behavior that she sees around her. Her interest in new technologies grew when she spent time in South Korea during the summer of 2014. Inspired by the constant stream of photos and videoclips on the internet, Joëlle Dubois confronts the viewer with explicit scenes of private life. By means of playful improvised compositions, she captures both the surfeit and the transient nature of the images. In her colorful figurative paintings on wood, she also deals with such topics as gender, sexuality and fetishism.

- Wouter De Vleeschouwer (S.M.A.K.) Juni 2016